By Kevin S. Giles

The other night I watched the original Psycho movie. It features Janet Leigh, Anthony Perkins, a lonely forbidding motel that a new highway bypassed, and a beckoning second-story light shining from a creepy Halloween-style house.

And there’s producer and director Alfred Hitchcock, the brain behind the 1960 movie’s tense scenes.

I can’t recall watching Psycho all the way through when I was younger. Maybe I stopped at the shower scene.

clearing up the mystery

This time, I paid attention to how Hitchcock crafted the plot. He started with a crime, invented an escape, confused the viewer with some misdirection and, finally, brought a psychiatrist into the final scene to explain what had happened.

When I began writing mysteries a few years ago, I learned it was no easy take to mimic the masters. I learned something else, too.

Mysteries, whether film or print, rely on formula plots. The basic structure involves a crime committed, a detective or other investigating hero introduced, and keeping the reader in the dark until the end. Hitchcock’s Psycho put to use a common technique in a mystery story — the summing up of all outstanding questions, usually described by someone central to the story or someone who emerges from outside the story to offer a clear-eyed explanation of what transpired.

In Psycho, it was the psychiatrist. In the Agatha Christie classic, Murder on the Orient Express, it was the protagonist Hercule Poirot.

I used a similar technique in my first Red Maguire novel, Mystery of the Purple Roses.

convincing characters make convincing mysteries

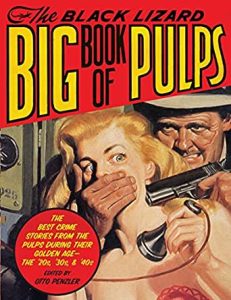

This mammoth compilation of crime stories from the pulp golden age contains stories from gifted writers such as Dashiel Hammett and Carroll John Daly. Photo by Kevin S. Giles from personal book collection

Authors make mystery stories unfailingly confusing if they deprive readers of occasional glimpses into the course of events. I personally prefer reading mystery stories that feature only a handful of key characters, as Psycho did, rather that trying to follow a long roster of suspects, as in Murder on the Orient Express.

Christie’s acclaimed novel took the reader in so many directions, casting suspicion on so many characters, that Poirot’s long summation at the end answered critical questions to save the reader deep frustration.

Frankly, readers don’t know what’s in an author’s mind. Nor should they.

I wrote both of my Red Maguire novels with that concern in mind. The author can’t become part of the story. The author makes characters work effectively, even burdening them with flaws, but they must feel like real people and speak for themselves.

In Mystery of the Purple Roses and the subsequent Masks, Mayhem and Murder, I tried to lead the reader to an ending that left no uncomfortable questions. Doing that, I discovered, requires an accomplished touch because a good mystery plot raises questions left and right.

Let’s hope I got the job done.

mysteries echo real life

Novelists often tell us how their characters come alive for them and become unpredictable in personality and behavior. That’s because as the author writes, and characters become more rounded, they become more capable. A character in a written plot outline is different from a character who is given a voice on a page.

Mystery writing evolves as characters take control and the plot twists into unexpected pitfalls and roadblocks. The successful author, and filmmaker, keeps the reader in the dark as the story unfolds but, at the end, also ties the loose ends into a nice bow.

I’m often struck at the similarity between fictional mystery and real life.

Crimes in the news start with the same vague facts. Somebody dies. Police search for the killer, often unidentified. Numerous theories come to light (most often in missing persons cases) that leave us contemplating who did the awful deed. When police solve the case (presuming they do), and it goes to court, we learn through a criminal complaint and jury testimony just how the crime unfolded.

television thrives on mysteries

The same formula plays out dozens of times a night on television. Every police, detective and court show has worked the same theme for decades because people love trying to solve crimes.

Even Perry Mason, a 1950s-60s hit drama, still airs on cable. The role by Raymond Burr dramatizes detective fiction written by Erle Stanley Gardner, one of the best-known “pulp fiction” writers. Good mysteries easily adapt from print to screen.

I imitated the pulp fiction genre in my Red Maguire novels. The gritty mining city of Butte, Montana, offered an ideal setting for the type of cloak-and-dagger exploits common in the pulps.

Pulp fiction magazines prospered into the 1950s before television took over crime drama. It was all about hard-boiled detectives and nefarious killers, buttoned-up do-gooders and troublesome villains, two-timing blondes adorned in flashy jewelry, and confidence men who chase after them. In my imagination, pulp fiction matched Butte’s personality. So I went with it.

find a niche, tell a story

This quote from Masks, Mayhem and Murder, spoken by protagonist Maguire, demonstrates the pulp fiction style of the novel:

“Been writing crime too long in this town to think otherwise, Babe. Sometimes I get lousy ideas about big trouble. Sure, I bet next month’s rent that all these two-bit jokers in masks take orders from Dregovich. What for? Only lonely men and fools lean into stiff wind.”

Styles differ in mystery writing and movie directing. Hitchcock differs from Christie. They both differ from Gardner and the dozens of other pulp writers.

Everyone telling mystery stories finds their way.

Writing mysteries, I discovered, feels like walking down a dark alley at midnight with a gun in one hand and the other groping for worn brick. You never know which hand you’ll need first.

Order Kevin's books now and receive a 10% discount by entering code "SaveOnKevinsBooks"

Western Montana native Kevin S. Giles wrote the popular prison nonfiction work Jerry’s Riot, the coming-of-age novel Summer of the Black Chevy, and a biography of Montana congresswoman Jeannette Rankin, One Woman Against War, which is an expanded version of his earlier work, “Flight of the Dove.” His new novel, Headline: FIRE! is the third in the Red Maguire series. Masks, Mayhem and Murder is the second. The first is “Mystery of the Purple Roses.” More information is available at https://kevinsgiles.com.

Kevin ~

Just received your second book on Red’s adventures in Butte. So excited to read in the coming weeks.

You are my hero!

Suzanne

Thanks, Sue. Who knows what Red will do next.